Rewiring Royalties: How Streaming Befuddled Copyright.

- Peter Cousens

- Sep 17, 2025

- 12 min read

Creative artist Keith Richards from the band the Rolling Stones told Fortune magazine in 2002, that his greatest source of income was: ‘Performing rights. Every time it’s played on the radio I go to sleep and make money.’[1] Those were the days that have now become a distant dream for the majority of artists in today’s era of streaming. It is so distant that the role of copyright as a legal and moral protector of creative work seems to have unravelled. In fact, there are so many legislative loose ends that its inner workings are extremely difficult to comprehend. Loose ends, tangles and loopholes into which powerful players have hidden and colluded and ultimately bamboozled others on their way to extraordinary enrichment and control.

My apologies to Shakespeare but ‘there is something rotten’ with the state of copyright.[2]

To understand the unravelling and the wrong, we need to try to understand how copyright once worked. Oh yes, and how digital technology in the hands of opportunists has befuddled the law of copyright for the benefit of a voracious few.

Artists once sold physical copies of their songs on CD and vinyl. For every $AU25 CD retail sale they may have received an approximate 20% split with their record label.[3] Their songs were also broadcast on radio. For every radio broadcast of their song an artist received a share of an ‘equitable remuneration (ER),[4] from the performer’s ‘communicating to the public’ royalty.[5] This was a statutory right that the performer cannot be contracted out of.[6] The ER payment was and still is a 50/50 royalty split between the performer and the copyright owner of the sound recording (the master).[7] The royalty payment occurred when a song, in the form of a commercially produced sound recording was played in public or communicated to the public[8] via radio. Royalties were collected by Performing Rights Organisations (PRO’s) who were legally obliged to collect payments from broadcasters such as radio and television stations; live event producers; and venues such as shops and cafes.[9]

Across the world these PRO’s or intermediaries facilitated the flow of copyright royalties. Royalties for the sound recording (master); the lyrics and melody (musical work); and a royalty for reproducing a song or composition (mechanical); all flowed to the receiving entities – the record labels, performers, songwriters and music publishers. The size of the distribution was dependent upon the legal contracts between entities and the equitable remuneration mechanism that supported the performers on sound recordings. Let’s not forget that PRO’s themselves also collected fees of between 20% and 40% for ‘operational costs’.[10]

There were, even then, a lot of pieces of the pie to distribute.

This is how the majority of artists in the pre-digital age received an income. In simple terms – from royalties and sales. Remember that under copyright performers had and still have a basic non-waivable right to share the license fees collected by PRO’s.[11] I reiterate, this is the ‘equitable remuneration’ for sound recordings (masters) that are broadcast or communicated to the public. Even if the artist signed a contrary contract with a label, the right could not be signed away. Nothing in the law of copyright has changed. In Australia these laws are still in play.

Yet the majority of artists in 2025 digital age believe that remuneration is inadequate from the streaming platforms. 87.6% of European artists surveyed stated that streaming and copyright revenues are unfairly distributed.[12] Only 7% of professional musicians in the UK admitted to making more £1,000 a year from streaming royalties’[13] Copyright was once an artificially complex bundle of rights and obligations with balanced and rewarding outcomes for rights holders. It has now detached itself from its historical foundations.[14] Across the globe in a short period of time, a widening intellectual property divide[15] that extends beyond international treaties,[16] is rapidly extinguishing what was once the creative vibrancy of the planets music culture.[17]

Why is this happening?

A great divide has evolved between creative artists and the Music Industrial Complex (MIC). The MIC is made up of Warner, Universal and Sony (The Big Three) [18] and the streaming platforms – YouTube, Pandora, Google, Deezer, Amazon, Apple Music, Tidal, Rhapsody and Xbox.[19] To fortify the divide the MIC does not acknowledge an artist’s value differentiation and excludes the artist from proportionate revenue sharing calculations.[20] This is why there has evolved a systemic underpayment of artists.[21] Copyright is supposed to reward creativity.[22] In our present streaming scenario copyright rewards are systemically directed toward the MIC and away from the artist.[23]

With the expansion of the divide the technology of streaming[24] has challenged the established relationship between copyright owners, intermediaries, service providers, and users.[25] Dahrooge points out that ‘Music streaming services have left the music industry at a crossroads.’[26] In 2024 in the USA streaming services grew to generate 84% of music’s revenue. Worldwide it grew to 69%.[27] By contrast less and less money was earned by creative artists who provided the content.[28]

This transformation has been so rapid copyright regulatory legislation internationally and domestically has not kept pace with the digital technology.[29] Article 9(1) of the Berne Convention is central to the music industry. [30] The United Nations has stated ‘that current streaming economics are destroying music worldwide, and points to the need for a new royalty system to pay artists more fairly.’[31] The Digital Single Market Directive was passed by the European Union in 2019 in support of the artist’s ‘unwaivable rights and equitable remuneration.’ [32] Only Spain, Belgium and Uruguay have implemented laws to fulfil the directive.[33]

This delay, however, has allowed the streaming platforms, particularly Spotify to use the advent of streaming services and the growth of consumer subscribers, to bamboozle the music content creators and disrupt the way revenue flows.[34]

Spotify from the very beginning categorised on demand streaming as ‘making available’ content for consumers to choose what to listen to. This is a different category to ‘communication of content to the public’ which legally attracts ‘equitable remuneration’ – a familiar concept in this tale of woe. The distinction is crucial.[35] Spotify used the copyright categorisation to deprive artists of any equitable remuneration for the streaming of a song. Within the MIC, deals were quickly struck with The Big Three who achieved an 18% ownership, in support of Spotify’s growth.[36] Spotify took advantage of the support; the unregulated landscape;[37] the lack of a central data base to track copyright; and the speed of change.[38] It was a perfect storm, to the extreme detriment of the majority of world’s creative musical artists.

Here's how the detriment works.

Spotify has an annual revenue of $4.99 billion through its paid subscribers.[39] For every one-dollar Spotify receives in subscriptions the division of the profit is approximately 58.5 cents to master rights holders – Warner, Universal and Sony; 29.38 cents to the streaming service – Spotify; 6 cents to publishers for mechanical copyright; and 6.12 cents for performance royalties distributed to songwriters and performers by a PRO.[40] Overall, 70% of the $4.99 billion is divided between all categories of rights holders and intermediaries. In comparison ‘Spotify pays $0.00437 per average play, meaning that an artist will need roughly 336,842 total plays to earn $1,472’.[41]

It is at this point that the collusion between The Big Three and the intermediaries is at its most sophisticated. With digital technology unsupervised by competition or regulation,[42]Warner’s, Universal and Sony, audaciously became owners of the major publishing and performance rights organisations. Due a veil of secrecy and lack of transparency,[43]they legally manufactured a state of vertically integrated control over royalties and licenses to further disadvantage the creative artist.[44] This refinement of the law has been elegant and precise.[45]

To put this into a larger perspective the MIC controls the reproduction and distribution of most of the world's music. It controls the rights to over 10 million songs.[46] Worldwide legislative inaction favours the mechanisms that generate such control[47] and encourages a broader, and arguably dysfunctional, opaque global system. To add to the misery, technological companies – including the MIC – have become the tools that control the sale of data for the commodification of human behaviour.[48]

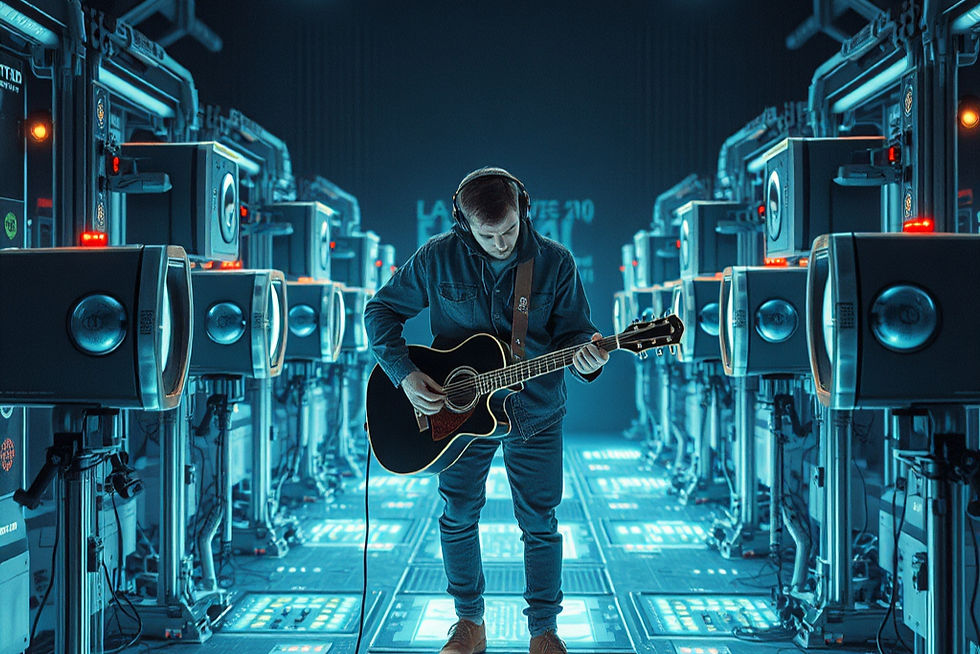

In this streaming dysphoria, copyright’s role now seems to be as the enabler of enormous digital economic interests and institutional power.[49] Concern for equitable remuneration for the creative artist becomes academic in this scenario. Creative artists have entered into digital servitude where their creative labour is valued at next to nothing[50] and streamed for the convenience of the consumer and the voraciousness of the Music Industrial Complex.[51]

For the creative artist, ‘To be or not be’[52] has become a very real question.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Articles/Books/Reports

Bowrey, Kathy, ‘The Outer Limits of Copyright Law – Where Law Meets Philosophy and Culture’ (2011) 13(1) Law and Literature 1

Calboli, Irene, ‘Legal Perspectives on the Streaming Industry: The United States’ (2022) 70(Supplement_1) American Journal of Comparative Law i220

Collins, Steve, ‘Where There’s a Hit, There’s a Writ: Intersections of Songwriting and Copyright Law’ (2024) 69 Lied und Populäre Kultur / Song and Popular Culture 113

Dahrooge, Ashley M, ‘The Real Slim Shady: How Spotify and Other Music Streaming Services Are Taking Advantage of the Loopholes Within the Music Modernization Act’ (2020) 21(1) Journal of High Technology Law 88

Johansson, Daniel, Streams & Dreams: The Impact of the DSM Directive on EU Artists and Musicians, Part 2 (International Artist Organisation, 2024) https://www.iaomusic.org

Korkeakivi, Susanna, ‘The Expansion of Spotify and International Copyright Law: Impact on Artists’ (2021) Michigan Journal of International Law https://www.mjilonline.org/the-expansion-of-spotify-and-international-copyright-law-impact-on-artists/

Ku, Raymond Shih Ray, ‘The Creative Destruction of Copyright: Napster and the New Economics of Digital Technology’ (2002) 69(1) University of Chicago Law Review 263

Lazar, Seth, ‘Governing the Algorithmic City’ (2023) 40(3) Philosophy and Public Affairs 239

Morrow, Guy, ‘Australia’s Performing Rights Organisation: Incentives, the Agency Problem and MetaGen’ (2025) International Communication Gazette (online) 1–16

Nycyk, Michael, ‘From Data Serfdom to Data Ownership: An Alternative Futures View of Personal Data as Property Rights’ (2020) 24(4) Journal of Futures Studies 25, doi:10.6531/JFS.202006_24(4).0003

Reuters, Music Revenues Rise Again in 2024, Boosted by Streaming Subscriptions, Report Shows (19 March 2025) https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/music-revenues-rise-again-2024-boosted-by-streaming-subscriptions-report-shows-2025-03-19/

Ramesh, S, ‘The Economics of Music Streaming: Impact on Artist Compensation and Industry Structure in the Digital Era’ (2024) 4(6) Journal of Humanities, Music and Dance 1 https://doi.org/10.55529/jhmd.46.1.8

Robinson, Dom, ‘The Economics of Music: Streaming vs CD Sales—A Deeper Look’ Streaming Media (online, 28 August 2024)

Rose, Meredith Filak, Streaming in the Dark: Competitive Dysfunction Within the Music Streaming Ecosystem (Berkeley Journal of Entertainment & Sports Law, May 2024)

Rogers, Jim, Sergio Sparviero and Patrik Wikström, ‘Royalty Collection Organizations: Private Interest Enterprises or Social Purpose Organisations?’ (2022) 10(1) The Political Economy of Communication 43

Rose, Meredith Filak, Streaming in the Dark: Competitive Dysfunction Within the Music Streaming Ecosystem (Paper, Berkeley Journal of Entertainment & Sports Law, May 2024)

Senftleben, Martin and Elena Izyumenko, Author Remuneration in the Streaming Age – Exploitation Rights and Fair Remuneration Rules in the EU (Joint PIJIP/TLS Research Paper Series No 137, October 2024)

‘The Brennan Bill — Royalties and Music Streaming in the United Kingdom (UK) and the Australian Context’ (2022) 34(9) Intellectual Property Law Bulletin 164

United Kingdom, Parliament, House of Commons, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, Economics of Music Streaming, Second Report of Session 2021–22 (HC 50, 15 July 2021)

United Musicians and Allied Workers, Summary of UN Report on Streaming (Web Page) https://weareumaw.org/un-report.

Weatherall, Kimberlee, ‘Of Copyright Bureaucracies and Incoherence: Stepping Back from Australia’s Recent Copyright Reforms’ (2007) 31 Melbourne University Law Review 967

Weatherall, Kimberlee G, ‘So Call Me a Copyright Radical’ (2011) 29 Copyright Reporter 123 (Sydney Law School Research Paper No 12/44, 5 July 2012)

Xalabarder, Raquel, The Principle of Appropriate and Proportionate Remuneration of Art 18 Digital Single Market Directive: Some Thoughts for Its National Implementation (Working Paper, August 2020)

Yu, Peter K, ‘The Copyright Divide’ (2003) 25(1) Cardozo Law Review 331 https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/540

C Legislation

Copyright Act 1968 (Cth)

D Treaties

Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, opened for signature 9 September 1886, 828 UNTS 221 (entered into force 5 December 1887) http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/treaties/text.jsp?file_id=283693

E Other

Association of Independent Music (AIM), Observations on DCMS Committee Inquiry: Impact of Streaming on the Future of the Music Industry (Press Release, AIM via Independent Music Insider) https://independentmusicinsider.com/press-release/economics-of-music-streaming-inquiry-evidence-comment-from-aim/

Bremmer, Ian, ‘What Is a Technopolar World?’ GZERO (online, 30 August 2023) https://www.gzeromedia.com/ai/what-is-a-technopolar-world

Competition and Markets Authority, Music and Streaming Market Study Update: Executive Summary (Research Paper, 26 July 2022) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/music-and-streaming-market-study-update-paper

Dent, Mark, ‘Spotify’s Recent Joe Rogan Controversy Has Also Deepened a Rift Between the Platform and Artists Over Pay’ The Hustle (online, 6 February 2022; updated 24 June 2024)

Houghton, Bruce, ‘60,000 Tracks Are Uploaded to Spotify Every Day’ (25 February 2021) Hypebot (online) https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2021/02/60000-tracks-are-uploaded-to-spotify-every-day.html

Houghton, Bruce, ‘Just 7 500 Artists Make $100 K or More a Year on Spotify Worldwide’ (24 February 2021) Hypebot (online) https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2021/02/just-7500-artists-make-100k-or-more-a-year-on-spotify-worldwide.html

International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), Industry Data – Global Growth by Region 2024 (Web Page) https://www.ifpi.org/our-industry/industry-data/

Music Business Worldwide, Spotify Posts $1.5bn Annual Operating Profit for 2024, as Subscriber Base Grows to 263m in Q4 (4 February 2025) https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/spotify-posts-1-5bn-annual-operating-profit-for-2024-as-subscriber-base-grows-to-263m-in-q4/

‘Rolling in the Money’ (Web Page, European CEO, 18 October 2012) https://www.europeanceo.com/lifestyle/rolling-in-the-money/

[1] ‘Rolling in the Money’ (Web Page, European CEO, 18 October 2012) https://www.europeanceo.com/lifestyle/rolling-in-the-money/ [Publishing: the next step].

[2] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, ed Harold Jenkins, Arden Shakespeare (Methuen, 1982) Act 1 Scene 4.

[3] Steve Collins, ‘Where There’s a Hit, There’s a Writ: Intersections of Songwriting and Copyright Law’ (2024) 69 Lied und Populäre Kultur / Song and Popular Culture 1, 22 (There’s a Writ).

[4] ‘The Brennan Bill — Royalties and Music Streaming in the United Kingdom (UK) and the Australian Context’ (2022) 34(9) Intellectual Property Law Bulletin 164 [3] (Brennan).

[5] Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 85 (1(c).

[6] Brennan (n 3)167[2].

[7] Ibid 163 [3].

[8] Ibid 164 [2].

[9] Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s 135ZZT.

[10] Dom Robinson, ‘The Economics of Music: Streaming vs CD Sales—A Deeper Look’ Streaming Media (online, 28 August 2024).

[11]Martin Senftleben and Elena Izyumenko, Author Remuneration in the Streaming Age – Exploitation Rights and Fair Remuneration Rules in the EU (Joint PIJIP/TLS Research Paper Series No 137, October 2024 1, 37[3].

[12] Daniel Johansson, Streams & Dreams: The Impact of the DSM Directive on EU Artists and Musicians, Part 2 (International Artist Organisation, 2024) https://www.iaomusic.org (Dreams).

[13] Brennan (n 3) 165[1].

[14] Kimberlee G. Weatherall, ‘So Call Me a Copyright Radical’ (2011) 29 Copyright Reporter 123, 123–33 (Sydney Law School Research Paper No 12/44, 5 July 2012) (Radical) 1 [2].

[15] Peter K Yu, ‘The Copyright Divide’ (2003) 25 Cardozo Law Review 331, 331 https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/540 (Divide).

[16] Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, opened for signature 9 September 1886, 1161 UNTS 30 (entered into force 5 December 1887) art 1–21 (‘Berne Convention’). Available at: https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/;World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Performances and Phonograms Treaty, opened for signature 20 December 1996, 2186 UNTS 203 (entered into force 20 May 2002).

[17] There’s a Writ (n 2) 1[1].

[18] Competition and Markets Authority, Research and Analysis: Executive Summary (26 July 2022) [4] (CMA).

[19] Dreams (n 11) 10 [2.2].

[20] Bruce Houton, '60,000 Tracks Are Uploaded to Spotify Every Day' (25 February 2021) Hypebot https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2021/02/60000-tracks-are-uploaded-to-spotify-every-day.html.

[21] CMA (n 17).

[22] Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘Of Copyright Bureaucracies and Incoherence: Stepping Back from Australia’s Recent Copyright Reforms’ (2007) 31 Melbourne University Law Review 967, 989 [3].

[23] Guy Morrow, ‘Australia’s Performing Rights Organisation: Incentives, the Agency Problem and MetaGen’ (2025) International Communication Gazette (online) 1, 1–16 (MetaGen).

[24] Bruce Houton, ‘Just 7500 artists make $100K or more a year on Spotify worldwide’(24 February 2021) Hyperbot https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2021/02/just-7500-artists-make-100k-or-more-a-year-on-spotify-worldwide.html.

[25] Meredith Filak Rose, Streaming in the Dark: Competitive Dysfunction Within the Music Streaming Ecosystem (Paper, Berkeley Journal of Entertainment & Sports Law, May 2024) 23,40[2].

[26] Ashley M Dahrooge, ‘The Real Slim Shady: How Spotify and Other Music Streaming Services Are Taking Advantage of the Loopholes Within the Music Modernization Act’ (2020) 21(1) Journal of High Technology Law 88, 201[2] (Shady).

[27]Industry Data Global Growth by region 2024 https://www.ifpi.org/.

[28] Shady (n 25) 201.

[29] Susanna Korkeakivi, 'The Expansion of Spotify and International Copyright Law: Impact on Artists' (2021) Michigan Journal of International Law https://www.mjilonline.org/the-expansion-of-spotify-and-international-copyright-law-impact-on-artists/ (Impact).

[30] Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and ArtisticWorks, opened for signature Sept. 9, 1886, S. Treaty Doc. No. 99-27, 828 U.N.T.S. 221 (1886), http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/treaties/text.jsp?file_id=283693.

[31] United Musicians and Allied Workers, Summary of UN Report on Streaming (Web Page). https://weareumaw.org/un-report (United Musicians).

[32] Ibid.

[33] Raquel Xalabarder, The Principle of Appropriate and Proportionate Remuneration of Art.18 Digital Single Market Directive: Some Thoughts for Its National Implementation (August 2020), 61.

[34] Shady (n 25) 215[2].

[35] UK, Parliament, House of Commons, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, Economics of Music Streaming, Second Report of Session 2021–22 (HC 50, 15 July 2021).

[36] Mark Dent, ‘Spotify’s Recent Joe Rogan Controversy Has Also Deepened a Rift Between the Platform and Artists Over Pay’ The Hustle (online, 6 February 2022; updated 24 June 2024) https://thehustle.co/the-economics-of-spotify 5.

[37] Shady (n 25) 201[1].

[38] Guy Morrow, ‘Australia’s Performing Rights Organisation: Incentives, the Agency Problem and MetaGen’ (2025) International Communication Gazette (online) 1, 1–16 (MetaGen).

[39]International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), Industry Data – Global Growth by Region 2024 (Web Page) https://www.ifpi.org/our-industry/industry-data/

[40] Irene Calboli, ‘Legal Perspectives on the Streaming Industry: The United States’ (2022) 70(Supplement_1) American Journal of Comparative Law i220, i235 (note 107).

[41]Shady (n 25) 88, 212.

[42] Lina M Khan, 'The Separation of Platforms and Commerce' (2024) 119(4) Columbia Law Review https://columbialawreview.org/content/the-separation-of-platforms-and-commerce/.

[43] Dark (n 30) 46.

[44]Meredith Filak Rose, Streaming in the Dark: Competitive Dysfunction Within the Music Streaming Ecosystem (Berkeley Journal of Entertainment & Sports Law, May 2024) 37[3] (Dark).

[45] Ian Bremmer, 'What Is a Technopolar World?' GZERO (30 August 2023) https://www.gzeromedia.com/ai/what-is-a-technopolar-world (Technopolar).

[46] Dark (n 41) 37[3].

[47] Kathy Bowrey, ‘The Outer Limits of Copyright Law – Where Law Meets Philosophy and Culture’ (2011) 13(1) Law and Literature 1, 78 (Outer Limits) 85 [2].

[48] Nils Aoun, Chloé Currie, Ava Harrington, and Cella Wardrop, 'Discover Weekly: How the Music Platform Spotify Collects and Uses Your Data' (Montreal AI Ethics Institute) https://montrealethics.ai/discover-weekly-how-the-music-platform-spotify-collects-and-uses-your-data/.

[49] Jim Rogers, Sergio Sparviero and Patrik Wikström, ‘Royalty Collection Organizations: Private Interest Enterprises or Social Purpose Organisations?’ (2022) 10(1) The Political Economy of Communication 43.

[50] Michael Nycyk, ‘From Data Serfdom to Data Ownership: An Alternative Futures View of Personal Data as Property Rights’ (2020) 24(4) Journal of Futures Studies 25, DOI: 10.6531/JFS.202006_24(4).0003.

[51] Raymond Shih Ray Ku, ‘The Creative Destruction of Copyright: Napster and the New Economics of Digital Technology’ (2002) 69(1) University of Chicago Law Review 263.

[52] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, ed Harold Jenkins, Arden Shakespeare (Methuen, 1982) Act 3 Scene 1.

Comments